OUR APRIL 7, 2019 SPRING TOUR

RESERVATIONS ARE NECESSARY IF YOU WANT TO ATTEND

On April 7, 2019 we will host a tour of the former E & K (Engels & Krudwig) Winery at 224 E. Market St. After the tour, join us for a social hour at the Bait House. We met at 3:00 at the winery building – use the door on the FAR LEFT. Park in the lot on the left side of the building or on the street.

Please note — the tour is limited to 25 people – if there is are enough people – a second tour at 4:00 will be held. These tours are very popular so reserve your spot today – the earlier you sign up the better.

Please note — the tour is limited to 25 people – if there is are enough people – a second tour at 4:00 will be held. These tours are very popular so reserve your spot today – the earlier you sign up the better.

In the meantime, here is a bit of history about the winery Sandusky’s love affair with wineries and breweries. Sandusky, and not surprising, ALL of Erie County has a rich history of grape growing and wine making. We even had our share of breweries.

At our spring meeting we will be touring the E & K winery building, formerly the Engels & Krudwig Winery.

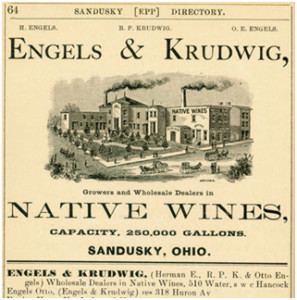

THE ENGELS & KRUDWIG WINERY

THE ENGELS & KRUDWIG WINERY

Herman Engels was born in Germany in 1827. He and his wife Louise immigrated to the United States in 1874. Herman’s uncle, Jacob Engels had come to the Sandusky area in 1848, where he became active in importing wine and in the culture of grapes. Jacob Engels founded the Engels Wine Company in 1863. After Jacob’s death in 1875, Herman Engels took over his uncle’s wine company. Herman’s children assisted their father with the business. In 1878 the firm became known as Engels and Krudwig, after R. P. Krudwig joined the company. Engels and Krudwig was located at the southwest corner of Water and Hancock Streets.

The Engels & Krudwig Winery, later the E & K Winery, was open from 1863 to 1959. During the 1850’s Jacob Engels began a wine import business. He planted a 10 acre plot of grapes to the east of the city in 1860 and began erection of the winery building in 1863. By 1878, Mr. R.P. Krudwig joined the Engels family in the flourishing business, and together they became the leaders in the burgeoning industry. By the turn of the century Engels & Krudwig Wines were famous across the eastern United States. Their native wines were being toasted as far east as New York City and as far west as Texas. The Engels and Krudwig families expanded their lines to include sparkling wines and vermouth, and with the erection of the distillation equipment, went into grape and fruit brandy production.

With prohibition threatening ruination of the business, The two families kept alive their tradition by the production of sacramental wines, de-alcoholized wines, and fresh grape juice. In 1934-1935, with prohibition behind them, Engels & Krudwig began its final major expansion. With the addition of 18,000 square feet, they became one of the largest wineries east of the Mississippi River. Total storage capacity, consisting entirely of white oak casks and cypress vats, was 868,000 gallons.

In 1959, after nearly 100 years of operation, the E & K Winery ceased production. The building is now occupied by Feick Contractors.

A LITTLE HISTORY ABOUT WINEMAKING IN THIS REGION

The history of Ohio winemaking can be traced back to the early 1800’s. It is believed that Nicholas Longworth, a lawyer from the Cincinnati area, saw the potential of the Ohio River Valley to become a major producer of wine. In 1820, he planted the first Catawba grapes. This domestic variety was hearty enough to withstand Ohio winters and the wine produced from it quickly won consumer acceptance. The light, semi-sweet wine was different from the other strong American wines of the day. Soon there were many acres of vines growing in the greater Cincinnati area and by 1845, the annual production was over 300,000 gallons.

By 1860, Ohio led the nation in the production of wine. Crop diseases, such as black rot and mildew, began to plague the grapes, the Civil War left the grape growers with little manpower.

Closer to home, first Kelley’s Island, then later the Bass Islands, began growing commercial grapes and then making and selling brandy and wine. the first Island grapes were planted in 1841 and Charles Carpenter produced the first barrel of wine in 1850. The Islands had a unique climate; the waters surrounding them provided a long growing season and insulated the vines from spreading disease.

Closer to home, first Kelley’s Island, then later the Bass Islands, began growing commercial grapes and then making and selling brandy and wine. the first Island grapes were planted in 1841 and Charles Carpenter produced the first barrel of wine in 1850. The Islands had a unique climate; the waters surrounding them provided a long growing season and insulated the vines from spreading disease.

Vineyards were soon planted on the Bass Islands and along the entire southern shore of Lake Erie. This narrow strip of shoreline soon became nicknamed the Lake Erie Grape Belt and officially designated The Lake Erie Aviticultural area. It includes 2,236,800 acres (905,200 ha) of land on the south shore of Lake Erie in the U.S. states of Ohio, New York, and Pennsylvania. Over 42,000 acres (17,000 ha) of the region are planted in grapevines, predominantly in the Concord grape variety.

Want to find out more? The Sandusky BlogSpot has several nice articles on some of the more prominent wineries including the Engels & Krudwig Winery that we will be visiting on April 7, 2019.

You can read more about these wineries:Engels & Krudwig, Edward Moos, Steuk Winery, Sweet Valley Wine Co., Engel’s Wine Co., the 1940 Ohio Grape Festival (Sandusky), William H. Mills.

THE TOUR CONTINUES WITH A SOCIAL HOUR

After our tour of the winery, we move on to beer and breweries at the BAIT HOUSE BREWERY

223 Meigs Street, Sandusky, Ohio 44870

419-502-HOPS (4677)

They are brewing in the Tap House adjacent to Herb’s old Bait Shop.

HISTORY OF BREWERIES ON THE SANDUSKY AREA

Not surprising, Sandusky was home to several landmark breweries. Here are some of the more noteworthy Sandusky brewers:

Kuebeler-Stang, Cleveland and Sandusky Brewing Company, and the Ilg Brewery

Ilg & Co. 1825-1890 established by Wilson Fox, it later merged into Strobel & Ilg and merged with the Kuebeler Brewery in 1890.

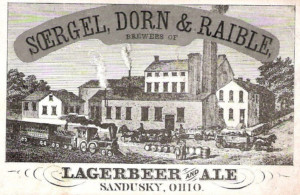

Soergel Dorn & Raible Brewery

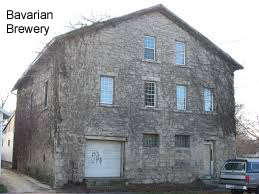

Bavarian Brewery – building is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Phoenix Brewery c1850 est. by John Strobel, merged in 1897 into the Cleveland & Sandusky Brewing Co.

Philip Dauch Brewing Co 1850-1862

Fox 1862-1863

Wilson & Fox 1849-?

Many of the bottles from these local breweries can be found in Erie County museums like this one on Kelleys Island.

Many of the bottles from these local breweries can be found in Erie County museums like this one on Kelleys Island.

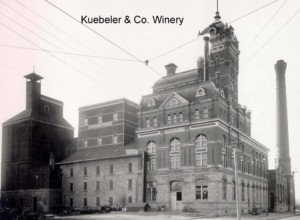

The Kuebler-Stang Brewery was one of the largest, and best known.

THE STANG BREWING CO., SANDUSKY, OHIO & THE CLEVELAND-SANDUSKY BREWING COMPANY

Sandusky’s longest lived brewing establishment appears to have begun operations as the City Brewery in 1852. Located on the east side of the north end of King Street (although in later years the plant had the address of 2207 W. Madison St.), the brewery was situated along the Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago, & St. Louis Railroad (also known as the Big Four RR.), just south of the Lake Erie shoreline. Phillip Dauch and Andrew Fischer were the original proprietors, although Dauch operated it alone after Fischer died in 1853. Dauch was a German immigrant who had landed in New York in 1847, and came to Sandusky by way of Cincinnati and Springfield, Ohio.

By 1862, he had encountered financial troubles and retired to a nearby farm, selling the brewery to John Bright, Lawrence Cable, & James Alder. They operated the plant until June 1868, when it was sold for $10,000 to George Windisch and Vincenz (Winsen) Fox, who had previously operated the nearby Ilg brewery. Fox sold an interest in the brewery to Frank Stang and John Homegardner in 1870, and two years later Windisch left the partnership.

In 1875, Fox declared bankruptcy, and the plant was sold at public auction to Stang and John Bender, a 55-year-old native of Baden, Germany. Bender began expanding the brewery’s annual output, doubling it from 3,000 to 6,000 barrels by 1878, the year in which he died. After this it remained in the name of his wife Magdalena (“Lena”) Bender for two more years. At that time, she sold the plant to Stang, who had been running the brewery after Bender’s death, for $30,000.

Frank Stang had been born in Monroeville, Ohio in 1851, and entered into the brewing industry after moving to Sandusky with his younger brother John. John was the traveling agent for the brewery, spending much of his time on the road until Frank withdrew from the company in 1890, after which John became the new president. Stang continued to increase the plant’s output, and by the late 1880s, the plant employed twenty men or more, including brewmaster Fred J. Beier, in producing between 15,000 and 20,000 barrels of beer annually. Seven teams of horses would deliver the beer in wagons throughout the city, with a great deal of additional brew being sent to surrounding counties. The stone brewery building was three stories in height, 225 by 250 feet in size, with a large attached ice house, capable of holding 10,000 tons of ice, which was cut from a nearby ice pond.

A disastrous fire in July 1891 destroyed virtually everything at the plant, including the office, malt house, ice house, ice machine, and most of the stored beer on hand, with a loss of over $100,000. Thought to be caused by a spark from the engine of a passing train, this exemplified one of the primary dangers of operating a brewery near a railroad, despite the obvious transportation advantage (a spark from another train five years later caused the destruction of another, newly built ice house at the site). While the nearby Kuebeler brewery agreed to temporarily fill all of Stang’s orders, the plant was completely rebuilt from the ground up over the next year.

On March 8, 1896, the Stang Brewing Co. merged with the Kuebeler Brewing and Malting Co. one mile away, forming the Kuebeler-Stang Brewing & Malting Co. Stang became the vice-president of this combine (Jacob Kuebeler was president), which had $700,000 in capital stock, and a collective annual capacity of 350,000 barrels. This entity lasted for less than two years before becoming a part of the Cleveland & Sandusky Brewing Co. conglomerate (which would eventually consist of eleven breweries in three cities) on January 1, 1898.

Stang continued to manage the plant, and eventually became vice-president of the parent company after Kuebeler’s death in 1904. The plant continued to operate very successfully as a division of Cleveland & Sandusky until 1919 (It should be noted that the two Sandusky plants continued to use the name Kuebeler-Stang for a number of years in their advertising, even after the formation of the Cleveland & Sandusky Co.)

Upon the enactment of statewide Prohibition in 1919, the Kuebeler plant was closed, leaving the Stang plant as the city’s only surviving brewery. It continued to operate throughout the next fourteen years, capitalizing on the name recognition of its flagship product by renaming itself as the Crystal Rock Products Co. (still a subsidiary of the Cleveland & Sandusky Co.) Crystal Rock Cereal Beverage, Deerfield Ginger Ale, and other soft drinks were produced through the end of Prohibition with a moderate degree of success. Stang had left the company by 1923 to manage a local wine company, after which the plant was managed by Roy Homegardner, who had been with the company since 1902.

With the repeal of Prohibition, the old Stang plant was refurbished as one of only two surviving branches of the Cleveland-Sandusky Brewing Co. (the other being the Fishel plant in Cleveland). In July 1933 it became the first of the two breweries to release beer to the public, when Gold Bond Beer was shipped east for sale in the Cleveland market, followed soon by Crystal Rock Beer, and three new brands, Old Timers and Buccaneer Ales and New York Special Beer.

Brewing operations continued successfully for two years until all of the plant’s eighty workers went on strike in April 1935, in connection with a massive brewery worker strike in Cleveland. The conflict was the culmination of a long standing battle for jurisdiction over brewery truck drivers, who had previously been members of the brewery workers’ union, but who had recently switched allegiance to the teamsters’ union. While the brewery owners were essentially neutral in this conflict, they ultimately paid the greatest price, as the breweries operated at a reduced capacity with replacement workers for several months.

The old Stang plant was particularly hard-hit, as clashes between strikers and replacement workers turned violent, with several people being injured in early May when a tear gas bomb was thrown. Rocks and stones thrown at the brewery broke windows and lights, and the plant shut down completely for two weeks. By the end of that month, manager Roy Homegardner announced that the plant would close permanently and the equipment would immediately be dismantled and moved to the main Cleveland plant (the only one remaining in the company). By the time the strike finally ended in November, Sandusky’s brewing history had come to a sad end.

The brewery stood empty for two years until the buildings and remaining equipment were purchased by local businessman Elliott M. Bender for $100,000. His plan was to sell $300,000 worth of stock in order to make the brewery operable again by the following summer. This plan never took shape, however, and as late as 1938, it was announced that the Sandusky Chamber of Commerce was still looking for a way to get the brewery back in operation. Instead, the plant remained empty for nearly a decade before the entire complex was razed in 1947, leaving no remains today.