FACER PARK

FACER PARK

In 2005, a group of young civic leaders in Sandusky initiated an effort to recognize the city’s role in the Underground Railroad. Facer Park, on the city’s waterfront, was chosen as the location for a sculpture and related educational displays. Over 50 local organizations, businesses and individuals were involved with the project. The park was dedicated on October 9, 2007. Created by local artist Susan Schultz, the sculpture is a symbolic representation of fearless people escaping the chains of slavery. The man’s outstretched arm shows they have almost reached freedom. The pedestal displays attempt to capture the history of the actual men and women, both black and white, all of whom wrote Sandusky’s Underground Railroad history through their courageous actions. Fugitives, the African American community, attorneys, ship captains and their crews all were integral parts of the “Path to Freedom.”

Find out more about Samuel Facer and Facer Park HERE

HARRIET BEECHER STOWE & UNCLE TOM’S CABIN

HARRIET BEECHER STOWE & UNCLE TOM’S CABIN

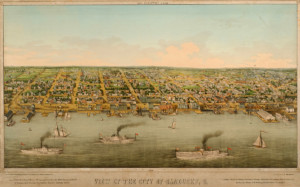

A decade before the Civil War, the Underground Railroad in Sandusky was a secret everybody knew. Slave catchers waited around Sandusky docks. So it was no surprise when a national bestseller about the Underground Railroad used the Sandusky docks as a setting in 1852.

In Uncle Tom’s Cabin, author Harriet Beecher Stowe has her fictional character Eliza don a disguise and board a Sandusky steamboat to Canada. According to the “President of the Underground Railroad,” Quaker Levi Coffin, the character Eliza was based on a real woman, a woman who truly escaped on a Sandusky steamboat.

A decade before the Civil War, the Underground Railroad in Sandusky was a secret everybody knew. Slave catchers waited around Sandusky docks. So it was no surprise when a national bestseller about the Underground Railroad used the Sandusky docks as a setting in 1852.

In Uncle Tom’s Cabin, author Harriet Beecher Stowe has her fictional character Eliza don a disguise and board a Sandusky steamboat to Canada. According to the “President of the Underground Railroad,” Quaker Levi Coffin, the character Eliza was based on a real woman, a woman who truly escaped on a Sandusky steamboat.

The character of Uncle Tom, from Stowe’s fictional book, was also based on a real person. Harriet Beecher Stowe had read the autobiography of Josiah Henson and was impressed by the Christian virtues he displayed as he recounted his experiences as a slave. So she used Henson as a model for her character, Uncle Tom, and also for her character George Harris. In Stowe’s book, Uncle Tom dies a tragic death. In real life, Josiah Henson and his family safely escaped to Canada, like George Harris did, where they built a new life for themselves. Josiah Henson explains in his autobiography how he and his family escapes passing through the area a few miles to the west of Sandusky, and getting on a ship in Sandusky Bay.

The character of Uncle Tom, from Stowe’s fictional book, was also based on a real person. Harriet Beecher Stowe had read the autobiography of Josiah Henson and was impressed by the Christian virtues he displayed as he recounted his experiences as a slave. So she used Henson as a model for her character, Uncle Tom, and also for her character George Harris. In Stowe’s book, Uncle Tom dies a tragic death. In real life, Josiah Henson and his family safely escaped to Canada, like George Harris did, where they built a new life for themselves. Josiah Henson explains in his autobiography how he and his family escapes passing through the area a few miles to the west of Sandusky, and getting on a ship in Sandusky Bay.

FRANCIS DRAKE PARISH

FRANCIS DRAKE PARISH

Francis Drake Parish was born in Upstate New York in Ontario County in 1796. He worked as a teacher and then studied law in Columbus, Ohio. He organized the Firelands first temperance society. He was also one of the organizers of the Erie County Agricultural Society. At first, he strongly opposed helping freedom seekers. In fact, Parish represented the claimant in the Benjamin Johnson case, the landmark case in which Lucas Beecher defended Johnson and won. Until 1835, Parish opposed abolition and was a member of the Colonization Society. After a change of heart he was so fervent about the cause the he was threatened with the destruction of his property and personal violence. It was even said that he should be ridden out of town on a rail. In spite of this, he showed no fear, and harbored many freedom seekers in his home. After he became an abolitionist, it was said that he was as zealous in the cause as William Lloyd Garrison. In 1836, he represented Sandusky at the first annual Ohio Anti-Slavery Convention, where he presented a resolution attacking the unfairness of existing Ohio laws with reference to black and mulatto persons.

The Sandusky Docks

The Sandusky Docks

View from Confederate Prison. This is a contemporary view of the Sandusky skyline as seen from Johnson’s Island, site of a prison for Confederate officers during the Civil War.

View from Confederate Prison. This is a contemporary view of the Sandusky skyline as seen from Johnson’s Island, site of a prison for Confederate officers during the Civil War.

There were several individual escape attempts and a few were successful. There was one organized attempt in September,1864, involving a plan for Canadian-based Rebel spies and sympathizers lead by Virginian John Yeats Beall to seize the warship U.S.S Michigan, which was anchored in Sandusky Bay, turn its guns on the guard at Johnson’s Island, and then free the prisoners who could escape to Canada. The attempt failed when U.S. forces were made aware of the plot in advance. After the escape attempt, artillery batteries were added to Johnson’s Island and Cedar Point to guard the entrance to Sandusky Bay.

While summers were pleasant, winters were difficult for Southerners unused to a Great Lakes climate. Although conditions were hard, Johnson’s Island was one the best run Civil War prisons (North or South) and had one of the lowest death rates of any Civil War prison. Approximately 250 prisoners died there during captivity. Some were eventually returned to their homes after the war; however, 212 are buried at Johnson’s Island. The cemetery is maintained by the Federal government and open to the public.

In 1910, a monument to the deceased soldiers was erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, Cincinnati Chapter.

For the past two decades, the prison site has been the object of a significant archeological investigation directed by Heidelberg University.