Although ravaged by the elements, there is a ‘rock’ in the downtown park which has an unusual history. On July 4, 1991 – the Erie County Historical Society dedicated one of its earliest plaques to explain this geological wonder. This history is ‘mostly’ taken from Janet Senne’s dedication speech, with a little more added.

This unusual geological formation is located in downtown Sandusky in Washington Park between Columbus Ave. and Wayne St., near the Gazebo. 41° 27.295′ N, 82° 42.589′ W.

This unusual geological formation is located in downtown Sandusky in Washington Park between Columbus Ave. and Wayne St., near the Gazebo. 41° 27.295′ N, 82° 42.589′ W.

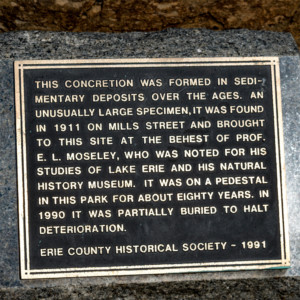

THE DEDICATION – “The Erie County Historical Society is represented here today to celebrate something in addition to Independence Day. We are here to dedicate a bronze plaque that explains the history of this large concretion. We are dedicating this marker to four people: Norbert Lange, who recognized the value of the stone; E. L. Moseley, who had it brought to the park; and Lynn and Mae Rosino,” who donated the funds for this plaque. The Erie County Historical Society is pleased that we can contribute something to this marvelous complex of parks that are the heart of Sandusky.

THE DEDICATION – “The Erie County Historical Society is represented here today to celebrate something in addition to Independence Day. We are here to dedicate a bronze plaque that explains the history of this large concretion. We are dedicating this marker to four people: Norbert Lange, who recognized the value of the stone; E. L. Moseley, who had it brought to the park; and Lynn and Mae Rosino,” who donated the funds for this plaque. The Erie County Historical Society is pleased that we can contribute something to this marvelous complex of parks that are the heart of Sandusky.

WHAT IS A CONCRETION? – While it looks like just a big, round rock, concretions are unusual and interesting geological occurrences. Concretions are formed in limestone, sandstone or shale. They are usually formed around a fossil and some contain iron ore.

IT ALL STARTED IN 1910

This archeological treasure has an interesting history. This article from the Sandusky Register of  tells how the ball was found embedded in clay about 12 feet underground while workmen were excavating for the boiler room of the new Hinde and Dauch plant at the foot of Jefferson St. on Mills.

tells how the ball was found embedded in clay about 12 feet underground while workmen were excavating for the boiler room of the new Hinde and Dauch plant at the foot of Jefferson St. on Mills.

Many thought the object had fallen from the sky, and some even remembered that some time before, a meteor had been seen in that location falling to the earth and that a boom like a cannon had been heard. But Professor Moseley, a prominent scientist and high school teacher in Sandusky, said that it was a concretion, formed in shale and transported many miles by the glacier to where it was found. Several city officials proposed that it would be a good idea to set this 4-ft. foot diameter ball on a pedestal in one of the parks with an appropriately inscribed base.

The Professor, thinking that this was something that he might use in his Natural History museum, came with a small hand bag to carry it home. He was astounded at the size and began making arrangements to have it transported downtown.

Rail tracks ran near the construction site and a wrecking train with a crane was brought in to lift the specimen from the pit onto a flat car. It was taken to the front of Jackson St. Then from the railroad car it was lifted onto a so-called stone wagon, a low flat bottomed dray drawn by horses (which was owned by Edward Feick Sr.). The dray proceeded up the street until it reached the middle of the next block, when the 5 o’clock whistle blew. The men unhitched the horses and went home, leaving the stone on the dray. When they came back the next morning, the stone was split down the middle. Undaunted, Moseley had it hauled to Ed Hinkey’s blacksmith’s shop and an iron band was fastened around it, pulling it back together.

The dray finally moved the concretion to Washington Park near the old high school. It was then placed on a concrete base where it stood until last December (1990).

The February 11, 1911 Sandusky Star-Journal heralded this event – MUSEUM OPEN SUNDAY Huge Concretion On Exhibition In Front of Entrance to High School Building. The high school museum will be opened to the public, Sunday afternoon and those persons who visit there will be shown about the museum by high school instructors and students. [The concretion] recently unearthed at the Hinde Dauch property on the west end, will be on display in Washington park, just in front of the entrance to the museum. This big specimen, which was found 12 feet below the surface, was presented to the museum by J. J. Dauch. At present it is on a wagon but is later to be set up in the park on a concrete base, it is the best formed concretion ever [found] by Prof. Moseley, although not quite as large as some others he has found in the shale banks along the Huron river between Milan and Monroeville. Many smaller concretions are exhibited inside the museum. While these will be on display Sunday, Prof. Moseley will request that no questions be asked about concretions and their formation. He intends to take up this subject for discussion at a later public reception at the museum when 11 of the students in charge will be prepared to tell the entire story of concretional formations.

The High School building where Mosley had his museum still exists and is located on E. Adams Street, just east of the library. Today is better known as Adams Jr. High School. The part facing Washington Park in this postcard picture is still standing except for the building’s third floor and its two towers, which were removed during a renovation in 1977.

The High School building where Mosley had his museum still exists and is located on E. Adams Street, just east of the library. Today is better known as Adams Jr. High School. The part facing Washington Park in this postcard picture is still standing except for the building’s third floor and its two towers, which were removed during a renovation in 1977.

This undated letter from Norbert Lange, written to Joe Walter, tells how he persuaded the workmen not to demolish the rock and called Professor Moseley to come and see it. Lange noted that around 1934, 24 years later, people had forgotten the story and were wondering about the “big boulder” in Washington Park.

This undated letter from Norbert Lange, written to Joe Walter, tells how he persuaded the workmen not to demolish the rock and called Professor Moseley to come and see it. Lange noted that around 1934, 24 years later, people had forgotten the story and were wondering about the “big boulder” in Washington Park.

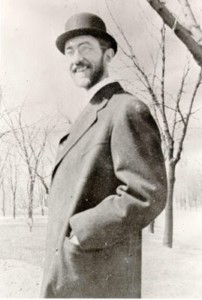

PROFESSOR MOSELEY – Moseley himself is not well remembered today. After teaching science at Sandusky High, he was recruited to BGSU, where he established the Natural Science Department. One report indicates that all of the artifacts in his Natural History Museum (except the concretion) were taken to BGSU with him when he began working there and that over time they deteriorated and were eventually thrown out by the university.

PROFESSOR MOSELEY – Moseley himself is not well remembered today. After teaching science at Sandusky High, he was recruited to BGSU, where he established the Natural Science Department. One report indicates that all of the artifacts in his Natural History Museum (except the concretion) were taken to BGSU with him when he began working there and that over time they deteriorated and were eventually thrown out by the university.

Moseley’s museum at Sandusky High School was first opened on Jan 1, 1891 after he received permission from the school board to use space in the old Sandusky High School (now better known as Adams Jr. High) to display it. The museum actually remained open there until December 1932, when the school board needed to take back the museum’s space for another classroom due to increased enrollment. From 1932-1938, the entire collection was stored in the high school building’s attic. Keep in mind that Moseley left Sandusky Schools in 1914 to join the faculty at Bowling Green State Normal College (now BGSU), so his collection was still in Sandusky after he left.

MOSELEY’S MUSEUM – Most of the artifacts (about 17,000 specimens according to Relda Niederhofer) in his Natural History Museum (except the concretion and a few other things) were eventually moved to BGSU in 1938 after Moseley was unable to find  a suitable space to display them locally. The collection was displayed at BGSU for a number of years (Relda Niederhofer writes in her book about how she was hired by the university to help maintain it during her time there as an undergraduate student in the 1940s), but it had long since been removed from public display. It is unclear whether his collection remains in part at the university. Since the concretion was originally placed in Washington Park as part of the museum, it is likely one of the last remaining existing artifacts from Mosley’s collection still in Sandusky.

a suitable space to display them locally. The collection was displayed at BGSU for a number of years (Relda Niederhofer writes in her book about how she was hired by the university to help maintain it during her time there as an undergraduate student in the 1940s), but it had long since been removed from public display. It is unclear whether his collection remains in part at the university. Since the concretion was originally placed in Washington Park as part of the museum, it is likely one of the last remaining existing artifacts from Mosley’s collection still in Sandusky.

The original science and agricultural building (recently heavily renovated) at Bowling Green is named for him and still in use.

As a side note, Prof. Moseley cataloged the first discovery of the Lakeside Daisy, an endangered plant. There are just two sites that the Lakeside Daisy can be found, and both are located in northern Ohio and protected: Marblehead on the Marblehead peninsula and the Kelleys Island State Park. This is a remarkable plant, growing only in quarry wasteland. Efforts to transplant this flower into a more hospitable environment is always met with failure. It only grows where there is literally no dirt.

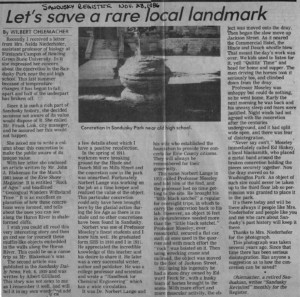

This November 1986 article, written by Wilbert Ohlemacher, responded to a letter he received from Relda Niederhofer. In that letter she expressed concerns about its deteriorating condition and asked if there was a way that it could be saved. The bottom was disintegrating and was becoming a danger so it was placed halfway into the ground which it was believed would halt further damage and preserve it for many more years.

This November 1986 article, written by Wilbert Ohlemacher, responded to a letter he received from Relda Niederhofer. In that letter she expressed concerns about its deteriorating condition and asked if there was a way that it could be saved. The bottom was disintegrating and was becoming a danger so it was placed halfway into the ground which it was believed would halt further damage and preserve it for many more years.

Janet Senne noted that there were concretions of similar size in Erie County. One was found at the former Perkins Township complex at 5420 Milan Road, and another was discovered at Pelton Park in 1990 (N of Great Wolf Lodge) while grading a parking lot. It was only a half, so the inside was clearly visible.

Finally, it is sad to see that the concretion that everyone worked so hard to preserve is gradually falling apart with age. This is a reminder that the history of many of our historic buildings and places need to be protected and the people of Erie County reminded of what a rich history we have.

Although nothing was done to explain what the big rock was, and why it was in the park, an article published on February 6, 1939 revisits its history and the process for moving the big rock with hopes of rekindling interest.

Although nothing was done to explain what the big rock was, and why it was in the park, an article published on February 6, 1939 revisits its history and the process for moving the big rock with hopes of rekindling interest.